I have just returned from Botswana, on a trip that turned into more of an adventure than we had planned. I’ll tell the story gradually, and I’ll start in the Makgadikgadi Pan grasslands, a vast plain with a 360 degree horizon:*

The endless vistas were covered in a tapestry of grasses and wildflowers, sometimes with flocks of tiny queleas:

The land is dotted with salt pans, a few with water,

but most dry:

The National Park itself covers nearly 5000 sq km, and the entire pan system is 16,000 sq km.

The flatness produces distorted mirage-like sunets:

I was with five friends, and our guide TJ, camping. For three days we saw not a single other human being or vehicle, our own private wilderness. Jane, who has eagle eyes, found us five giraffe, four of which are in this photo if you look hard:

As we got closer we got the once-over:

There were two adult females, and three youngsters, two of whom were very young indeed.

These are Southern Giraffe, widespread in Southern Africa. Adults can reach 6m (19 feet) and the babies are six feet tall at birth.

The two smallest are roughly the same age, so the likelihood is that they are from the two different mothers, since twins are extremely rare. One of them kept trying to nurse, and eventually its mother let her/him:

You can tell the sex of the adults by the state of their horns, or more precisely their ossicones. The males fight, so the tops of the horns quickly lose their hair and become shiny:

Males like the one above also have a third ossicone in the middle of their forehead that develops as a sort of callus from head-butting their rivals.

This video is of a male, showing both these badges of combat; the third ossicone can be seen in profile at the end of the video:

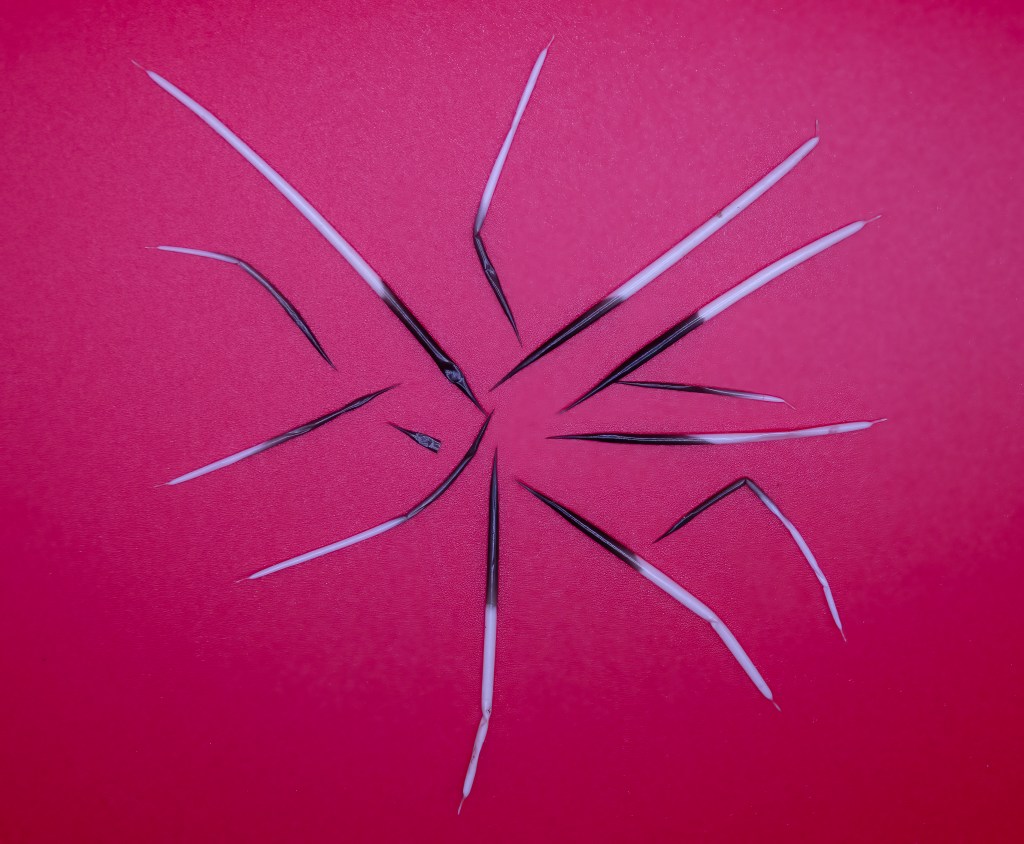

At birth the ossicones are cartilage, folded down, and then they straighten and harden as the animal grows. Something went amiss for this female, but luckily she doesn’t need them for fighting:

As the sun went down I stuck the camera out of the moving vehicle, and captured the flavor of the place.

PS Jane is using her phone to try and ID birdsong with Merlin, not to make a call. We were several hours drive from cellphone reception. Merlin was, sadly, pretty hopeless in Botswana