[I have just returned from The Gambia in West Africa, looking at birds with the photographer and guide Oliver Smart of Naturetrek. I’ll be doing several posts from the trip, perhaps interspersed with anything interesting in Maine now that I am back.]

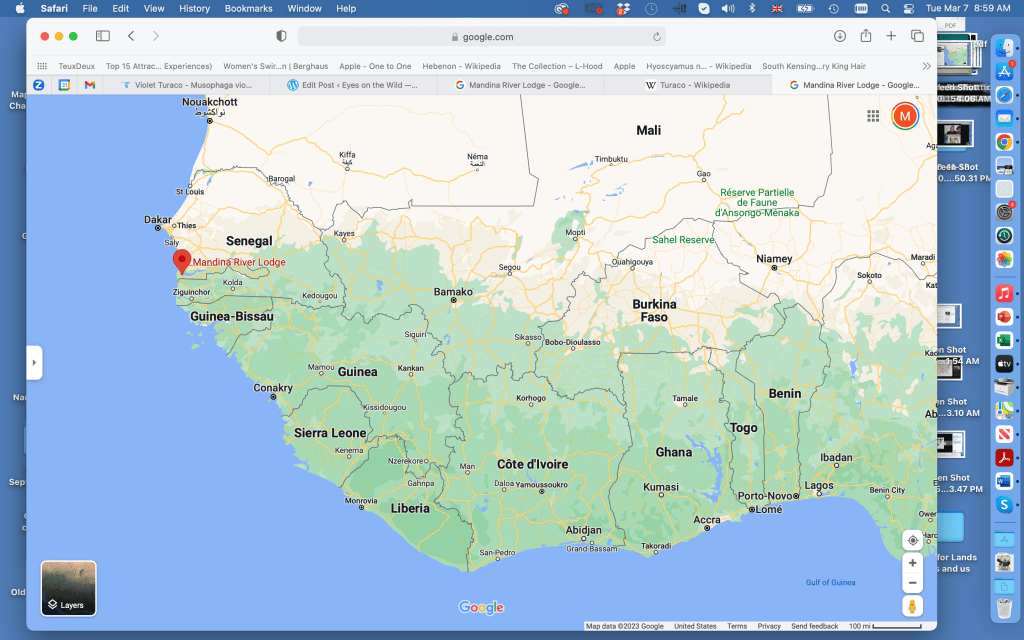

First, to situate you for the weeks ahead, here is a map showing where the Gambia is in West Africa. The red pin is our lodge, Mandina River Lodge.

The Gambia is a very unusual shaped country, along two sides of The Gambia river, and entirely surrounded by Senegal. The river is 10Km wide where we were, so there are no bridges until the 1.2 mile Senegambia bridge, 120 Km up-river, which opened in 2019.

So, on to the birds. These pictures were taken over several different encounters.

Sitting high in the tree was a plump purplish-black bird the size of a large pigeon with a long tail, a crimson head and a chunky reddish-orange bill:

It was a Violet Turaco, Musophaga violacea. The yellow forehead is a hard casque, and the red eye-ring is bare skin., which you can perhaps see better in the not-very-sharp photo below:

Weighing in at 360gm, and about 50cm long, its scientific name means “banana-eater”. It gorges when it finds a productive fruit tree, hanging upside-down if necessary to reach the ripest fruits, especially figs:

The flight feathers are deep crimson, visible in the next photo as it spreads its wings to keep its balance:

or on a short flight to a new branch:

But when it really takes off:

and spreads its wings fully, just look:

The crimson color is produced by an entirely different pigment from the reds of all other bird families, and called appropriately turacin. Hence my title.

Another oddity: it has ‘semi-zygodactylous’ feet: the fourth (outer) toe can be can be brought around to the back of the foot to nearly touch the first toe, or brought the front near the second and third toes. I failed to photograph this!

The Violet Turaco is not endangered and lives across a swathe of West Africa, but it has been little studied. The main threat seems to be the international trade in exotic birds: it is just too spectacular for its own good. In captivity they live a long time. The current record is 37 years.

I end with Herman Schlegel’s 1860 painting of a Turaco for the Royal Zoological Society – also known as Natura Artis Magistra, the oldest zoo in the Netherlands.