My game camera, positioned on a beaver trail, caught no beavers at all, but instead it caught a raccoon family hunting.

For anyone unfamiliar with raccoons, they are charming:

Nevertheless I know many people loathe them because they get into their trash and cause havoc, or indeed attack their bird feeders, as this video shows:

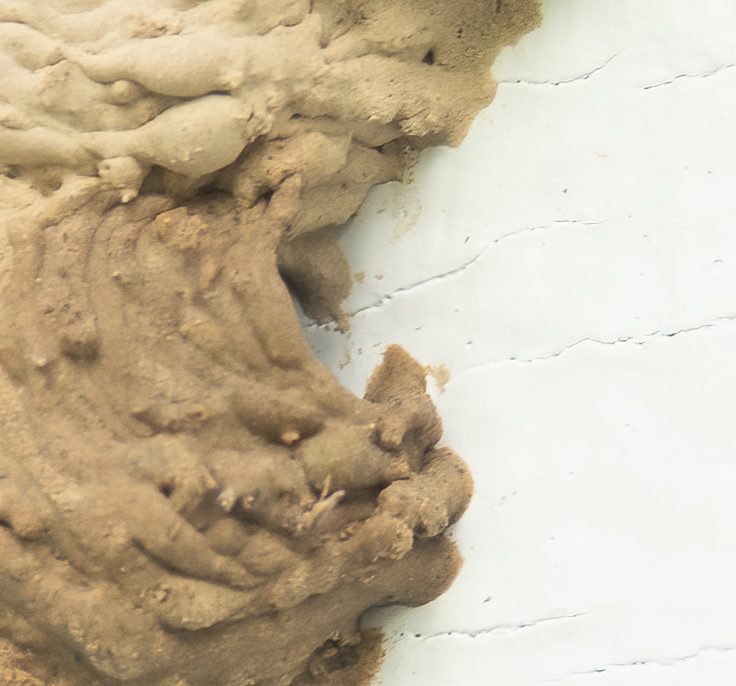

But those clever hands are designed for a different kind of foraging. In their natural habitat they eat aquatic invertebrates, like crayfish. They hunt at night, and have very sensitive forepaws, or hands, which they use to search in shallow water for their prey.

The video below was taken deep in the woods in the pool just downstream of a beaver dam. I have spliced together several videos. At first you see a single adult, questing for food at the water’s edge. Half way through, the adult is joined by four babies, each of whom is copying its parent’s technique. The mother and first baby appear together briefly at 22 or 23 seconds in, at the left of the frame, and then wander off, but there are three more babies to come.

You can see that they are not looking into the water (and anyway it’s nighttime!), but trusting entirely to their hands.

The moral of this tale is that if raccoons still have access to natural habitats, they sensibly prefer crayfish to garbage, as do the French, who particularly like theirs in a bisque .

(photo from https://honest-food.net/crayfish-bisque-recipe/ )

PS The five fingered raccoon forepaw, or hand, has no opposable thumb, but it can be used to grasp in several ways.

The diagonal lines show the different ways the hand can fold to grasp something, and the asterisk shows how they use a scissor grasp between two and three digits. (Drawing from Iwaniuk and Whishaw 1999.)

In addition they use both hands together, and roll food between them. The hand is especially sensitive when wet, and the fingers end in tiny vibrissae, or whiskers, that allow the raccoon to sense food without actually touching it. For those who enjoy a little more detail, Welker and Seidenstein 1959 studied how much of the sensory area in the cerebral cortex of a raccoon is devoted to its hands. The answer is a lot, nearly 4 times as much proportionately as in a rhesus monkey, for example. The brain has specialized areas for each digit, and also for five different areas of the palm. You can see why it is sometimes said that raccoons “see” with their hands.