Nowadays, jaguars are found from Mexico to Argentina, but there are none left in North America. So they are one of the most exhilarating animals to see on any South American trip. The ones in the Pantanal are some of the largest of all. A male can measure 2.5m and weigh 130Kg, with only lions and tigers being larger.

Finding them is not easy. Where we stayed, six are collared, and somewhat habituated to vehicles, so using a radio antenna it is possible to find them, but only if they cooperate. On one afternoon we narrowed a jaguar down to a clump of trees and scrub, and sat still for at least an hour hoping it would emerge, but it never did.

To collar a jaguar, the research team first find tracks or signs, then put up a camera trap to confirm its presence, then set a snare. They rush to the scene, tranquilize it, weigh it and take bloods, then collar it, and let it free. The next step is to find it again using the radio antenna, and get it used to seeing the vehicles, which can take a while.

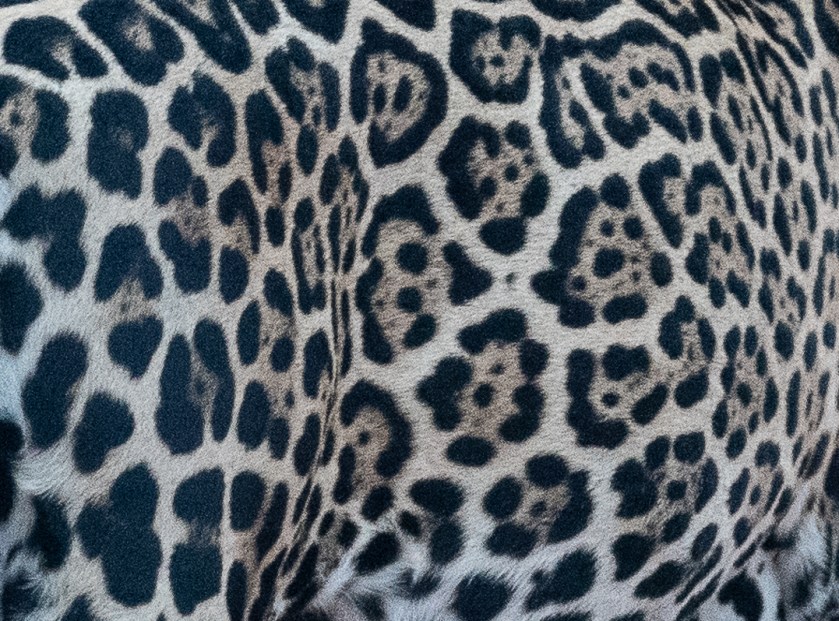

The team recognize the jaguars by their patterns of rosettes, distinctive for each animal:

Our best sighting was a mother, known as Suriya, and her one-year old female cub, Juba. (A male cub has already set off on his own.) The mother is collared, and habituated to vehicles. The cub is not collared, but stays with the mother. Here they are, cub in front and mother behind:

You can see the size difference more clearly in this shot:

They walked through the lush grass for a while:

then settled down in the shade of some trees:

Sporadic grooming followed:

After a while the bored youngster stalked and ambushed her snoozing mother (just visible deeper in the undergrowth):

Later, they encountered and startled a Pampas Deer in some bushes, but it escaped in the nick of time, unharmed.

In my second jaguar post I’ll talk about conservation concerns and projects, and introduce you to Acerola, a big male.

And I’ll leave you with this lovely 19th century image of the “South American Tiger”.