Floating at the edge of a beaver pond I found these delicate little Fringed Heartworts, Ricciocarpos natans, 5-15mm across, about 1/4″, with a beech leaf top left for scale. Each ‘leaf’ (more properly called a thallus) is an independent plant, and they are not rooted to anything, but bob around happily on the surface like little dodgem cars..

They are a type of liverwort, related to mosses, and like them the vast majority are terrestrial. But this tiny thing is nearly always aquatic, though the mystery deepens below.

I scooped out a cup of water with about eight tiny plants, and took it home for closer inspection. The leaf (thallus) has an underwater fringe of purplish strands, and the leaf surface is covered in minute air sacs, each divided from the next by a single-celled membrane, which help it stay afloat, but also have pores that allow it to take in CO2 for photosynthesis.

Each plant has both male and female organs , and it reproduces by abscission, in other words it keeps branching, and eventually divides into two, each becoming a new plant. The one at bottom right is about to divide.

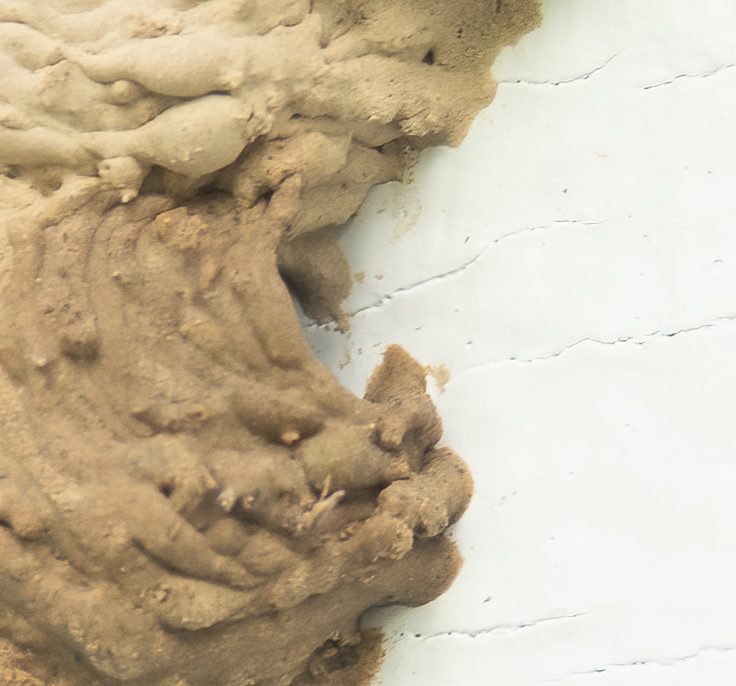

Underneath it looks for all the world like a Hawaiian hula skirt, or a tiny jellyfish (and in a dish when the water sloshes around they move in the most charming and animated way, so that it is quite hard not to mentally promote them from the plant kingdom to the animal kingdom):

The fringes are dark purple “scales” that act to stabilize it, and they can be up to 1/2″ long. They are very effective. When I casually tipped my cupful of plants into a new dish, every single one emerged from the turbulence the right way up.

Rather astonishingly, if its pond dries out, and it gets stranded on land, it stops growing scales, and roots itself in the earth by growing rhizomes instead.

Back in the pond, they provide a safe habitat for tiny invertebrates, sheltering them from the sun (or the bright lights of my kitchen), and hiding them from predators. In my scoopful of plants I inadvertently captured several of their charges.

Caught in the open, this mayfly larva scuttled back to the closest sheltering plant.

Another one had a minute caddis or stonefly larva underneath, which had decorated itself with a variety of things including what looks to me like a fragment of Fringed Heartwort leaf:

You could be excused for thinking it looks just as if the plant had captured this insect with a view to eating it, but they are not carnivorous, and the little caddis was swimming freely.

My final shot shows a translucent larva (on the left) of perhaps a Naidinae, something I had never seen before. Though it could just be a mosquito!

PS These Fringed Heartworts are found all round the globe, but they are thought to have split off from other lungworts after Pangaea split up, so they must have evolved on just one continent, and then they and their spores were carried across the world, probably on the plumage of birds.

This informative but rather technical article was very helpful in understanding this plant, by Singh, S. and B. Bowman (2023). “The monoicous secondarily aquatic liverwort Ricciocarpos natans as a model within the radiation of derived Marchantiopsida.” In Front. Plant Sci. Sec. Plant Development and EvoDevo. Volume 14 – 2023

All errors as always are my own!