[As was often the case on this trip, we couldn’t get close enough to the wildlife for me and my camera to get good shots. I’ve made a decision to write about some things anyway, because they are so interesting (I hope), but first I start with pictures that set the scene in Mongolian rural herding culture]

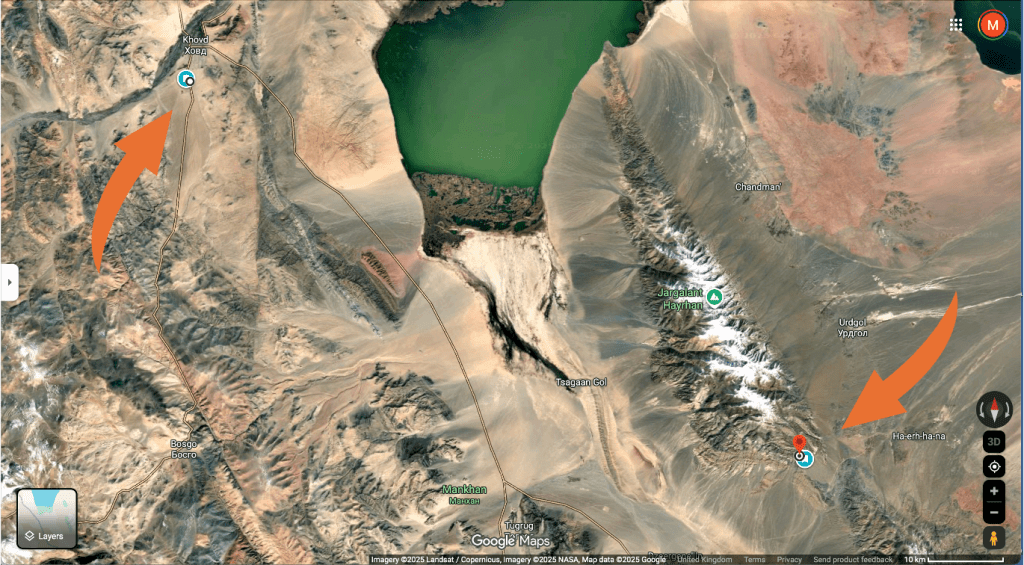

In the Mongolian Altai, down in the plains, there are large lakes, some of them freshwater and some saline. We visited both types. They’re very beautiful (but with a distressing amount of trash around). Most of these photos are of Khar-Us freshwater lake, 1800 Km2, average depth 2.1m. It is a national park.

The wind can be fierce, whipping up dust spouts:

The next photo is Dörgön Lake, a saline lake at 4% salinity, surrounded by samphire plants:

The local herders bring their livestock down to drink,

while they prefer to share a cup of tea with our drivers and Jane:

Back at Khar-Us lake, the braver waders browse on water plants:

The animals below are a mix of sheep and cashmere goats, now growing their winter coats; your next sweater “on the hoof”:

In the midst of this, there are waterbirds. Whooper Swans, Cygnus cygnus, breed here. They can be seen in the UK, but I have never seen one before. Their total range is from Iceland to Japan, and they only breed in the northern parts of that range. They have lovely yellow bills.

They graze on aquatic plants, in a behavior called, unimaginatively, “upending”!

They are thought to pair for life, but they are not well studied on their breeding grounds. This group of around twenty birds:

included two in the midst of a courting ritual.

Here’s a video:

I am happy to say they are not endangered. Soon after we saw them, they probably left for their wintering grounds further south.

Fifteen minutes later Istvan , with a note of excitement in his voice, said “Look, swan geese.” What? Which? Make up your mind. But I hadn’t misheard, there really is a bird called a Swan Goose, Anser cygnoides, which looks like a goose, but with a longer neck and a black (not orange) bill with a white line around it. In the picture below all but the leftmost goose (in both pictures) are Swan Geese. The outsider is a Greylag Goose.

They flew off before I could get better photos:

Second from left below could be a Swan Goose/Greylag hybrid.,

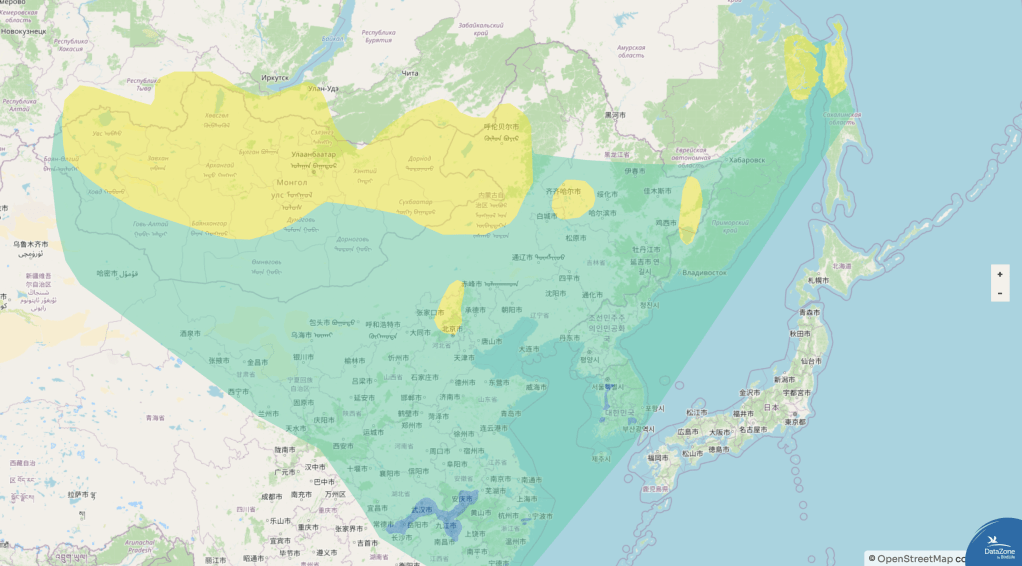

The reason Istvan was so excited is that Swan Geese are classified as Endangered by the IUCN. * Almost all of their breeding grounds are in Mongolia, the yellow areas on the map below:

They are protected in Mongolia, but in both their breeding grounds and their wintering grounds (mainly in China) their habitat is very much under threat, and hunting is also a problem. Overgrazing by livestock also plays a role, since the swan geese eat sedges and grasses too.

One final picture: a livestock enclosure on the shores, resourcefully and precisely made of mud brick masonry, dry stone walling, and discarded car parts:

In London or New York this would be considered an art installation.

* The Swan Goose conservation status has changed back and forth over the years, but the most recent listing is Endangered, see Birdlife International for details. The Birds of the World entry is out of date and under revision.